At the end of the 1840-s, Dostoevsky was preparing to go abroad: "How many times have I dreamed, since my very childhood, of visiting Italy. Beginning with Radcliffe's novels, which I read as early as when I was only eight years old, various Alphonses, Catarinas, and Lucias lodged themselves in my head And even now, I'm still crazy about Don Pedros and Donna Claras. Then came Shakespeare - Verona, Romeo and Juliet - the Devil only knows how great the enchantment was. To Italy, to Italy! But instead of Italy I wound up in Semipalatinsk, and before that in the House of the Dead".

Too often Dostoevsky turned up in a new place in spite of his own intentions. He loved Darovoe, but in the autumn all the children were taken back to Moscow He wanted to live in Moscow and study at the university, but his father sent him to Petersburg. He became used to Petersburg, which he associated with his career as a writer, but for reading just one forbidden text aloud he was punished monstrously, serving four years in a labor camp and roughly six years in exile. His motto "nothing is more fantastic than reality" was constantly proving itself: his reality was becoming a tragic farce. But even bound in chains and deprived of the freedom and solitude so necessary for his work, Dostoevsky was able to preserve not only his gift as a writer, but Ins love for mankind. Thus it happened that each tragic moment in Dostoevsky's life helped forge his personal convictions. At nineteen years old, when he learned of his father's death, he wrote in a letter to his brother, "Man is a mystery. It needs to be unraveled, and if you spend your whole life unraveling it, don't say that you've wasted time; I'm studying that mystery because I want to be a human being ". In ten years, when he was selling off for prison camp, Dostoevsky made his task more specific: "Life is life everywhere, life is in ourselves, and not outside There will be people by my side, and to be a human being among people and to remain one forever, no matter in what circumstances, not to grow despondent and not to lose heart-that's what life is all about, that's its task."

On the night of January 6, 1849, Dostoevsky-was sent from Petersburg to Siberia in a prison convoy. He was to spend four years in Omsk Prison: "I spent the entire four years in prison without going out, behind walls, and went out only for work. The work that fell to us was difficult... and on occasion I exhausted myself in bad weather, in the wet, in the slush, or in the wintertime in unbearable cold... We lived in a heap, all together in one barracks. Imagine for yourself an old, dilapidated wooden building that should have been torn down long since and that could no longer serve In the summer the .stuffiness is unbearable, m the winter the cold beyond enduring All the floors have rotted through. The floor is an inch thick with mud, you can slip and fall. The little windows are covered with hoarfrost, so that for the whole day it's almost impossible to read. There's an inch of ice on the windowpanes. There is a drip from the ceiling-it's all full of holes. We're like herrings in a barrel.... We slept on bare plank beds. One pillow was allowed. We covered ourselves up with short half-length fur coats and your feet are always bare all night. You shiver the whole night. Mountains of fleas, lice, and cockroaches... Add to all these delights the near impossibility of having a book, if you get one, you have to read it furtively, constant hostility and squabbling all around you, cursing, yelling, noise, clamor, always under guard, never alone, and four years of that with a change..."

Dostoevsky's years in prison camp seemed like a terrible dream. He wrote of himself as a "cast-off stone" or a " sliced-off crust": "And those four years 1 consider a time during which I was buried alive and locked up in a coffin.... It was inexpressible, unending suffering, because every hour, every minute weighed on my soul like a stone. In all those four years there was not a moment when I didn 't feel that I was in prison".

In Omsk the writer worked in a brick factory, baking and grinding alabaster; he labored in an engineering workshop and also shoveled snow from the city streets. Since it was forbidden to - write in prison, Dostoevsky's main creative work in Omsk was planning his future novels. All around him was a limitless supply of material for such plans. His first work, which he had been absorbing throughout all his four-year experience in prison, was a novel openly dedicated to the theme of the Russian prison, Notes from the House of the Dead. No city in which the writer lived was investigated and described in such detail as Omsk.

Life in prison for him was often unbearably difficult. When he returned to normal life, he didn't like to recall those years. In 1876, in Diary of a Writer, Dostoevsky admitted, "To this day that time comes back to me in my sleep sometimes and I know of no dream more tormenting". His own life had become material for his research. In prison he would recall his previous life, and fifteen years after his return from Siberia he would analyze the spiritual experience of the labor camp. In his meditations on the moral strength of the Russian people, Dostoevsky recalled one episode from prison life when he was particularly tired of his unruly neighbor prisoners and their drunken parties, and, as usual, decided to "return to childhood" in his thoughts. He "made his way to his place opposite the window with iron bars and lay on his back, with arms folded under his head and eyes closed..." This time he "suddenly recalled an incidental moment from early childhood ''At Darovoe, alone in a dense shrubbery, nine-year-old Fyodor had heard someone's cry, "A wolf is coming!" The peasant Marej, who was plowing the field, had comforted the frightened boy. "We were alone in that far and empty field, and only God above may have seen with what deep and enlightened feeling, with what delicate and almost womanly tenderness the heart of a rough savagely ignorant Russian serf could be filled... " This fleeting episode with the peasant Marej, insignificant in his adult consciousness, was an intense spiritual shock for the young Dostoevsky. The memory helped him survive in prison and not to lose faith in his people: "I remember I suddenly felt that I could now see these unfortunate people in quite a different light, that suddenly and miraculously all hatred and anger had vanished from my heart ".

In Omsk Dostoevsky lived behind a solid prison fence: "Looking through a chink in the stockade in the hope of seeing a bit of God's world, I would see nothing but a strip of sky and a high earthwork overgrown with tall steppe weeds, and the sentries who strode to and fro upon it night and day. And then 1 would realize that years would pass and I would still be peering through that chink, seeing the same earthwork and sentries and strip of sky, not the sky, above the prison, but the other, free sky far, far away... " Since he associated Omsk with the concept of prison, there was no way for him to like the town: "If I hadn't found people there I would have perished completely".

Fortunately, Dostoevsky always turned out to be near noble-hearted people who took an active interest in his life. In Omsk these were the soldiers and several of the office staff at the Main Government of Western Siberia. Dostoevsky was given particular attention by Altksei Fyodorovich de Grave - a commandant in the Omsk Fortress who tried to shelter the convicted writer from hard jobs and attempted to make his situation easier.

Having come into contact with the criminal world in prison, Dostoevsky came to terms with many abstract ideas about the intelligentsia and the common people, about crime and punishment, about freedom and its limits, as well as the problems of a strong personality. Dostoevsky described everything he had experienced during the Omsk years in Notes from the House of the Dead (published in I860, when the writer had already returned to Petersburg). In this book he not only depicted the mysterious world of prison camp, but for the first time so profoundly and intensely portrayed it in light of the problems facing Russian society as a whole. All his successive work was devoted to interpreting these "eternal questions".

While living here, on the banks of the Irtysh River, the writer never lost his hope for freedom In prison he existed in a perpetual state of expectation, dreaming of a new future. The writer gives these feelings to the hero of Crime and Punishment, Rodion Raskolnikov: "The day was again bright and warm. Early in the morning, at about six o 'clock, he went off to his work on the river-bank, where gypsum was calcinated in a kiln set up in a shed and afterwards crushed... Raskolnikov ... sat down on a pile of logs and looked at the wide, solitary river. From the high hank a broad landscape was revealed. From the other bunk, far way, was faintly borne the sound of singing. There, in the immensity of the steppe, flooded with sunlight, the black tents of the nomads were barely visible dots. Freedom was there, there other people lived, so utterly unlike those on this side of the river that it seemed as though with them time had stood still, and the age of Abraham and his flocks was still the present. Raskolnikov sat on and his unwavering gaze remained fixed on the farther bank; his mind had wandered into daydreams"

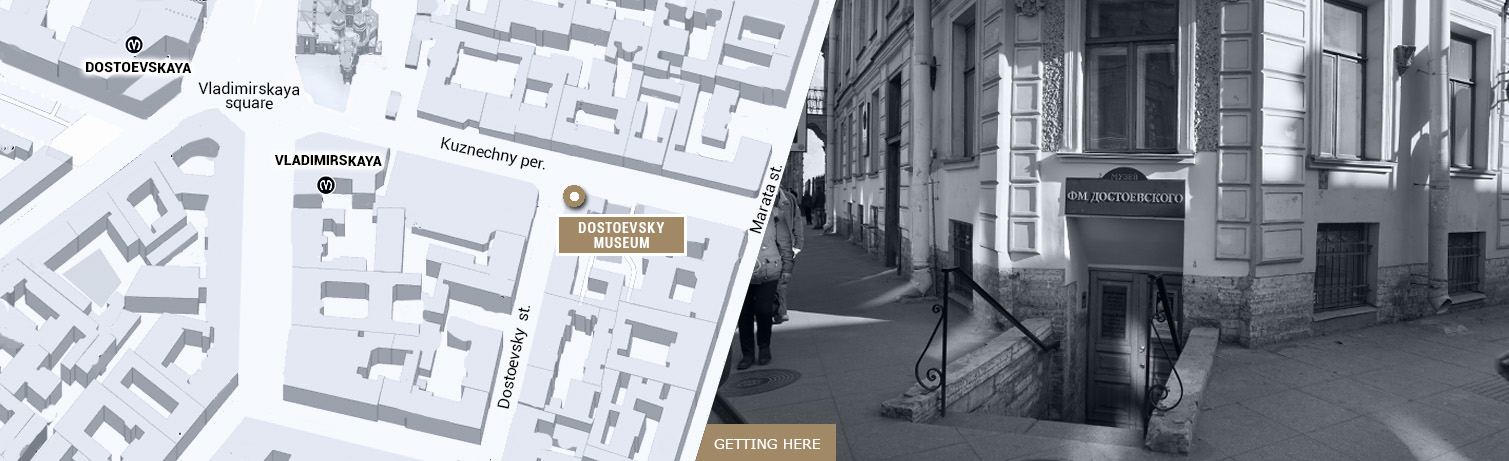

One of the oldest buildings in Omsk is the house constructed in 1799 for the commandants of the Omsk Fortress. In July of 1859 Dostoevsky visited the house as the guest of the last commandant, A.K. de Grave. On January 28, 1983, the P.M. Dostoevsky Literary Museum was opened here At first an affiliate of the Omsk State Museum of History and Literature, it gained independent status in 1991. The museum is devoted to the literary history of Siberia as whole. The central part of its collection, however, is dedicated to F.M Dostoevsky, and above all to the Omsk period of his biography (1850-1854). This exhibit is located in the main room, which served in de Grave's day as the sitting room where the commandant received Dostoevsky. The display there contains the first edition of Notes from the House of the Dead, issues of the journals Time, Notes from the Fatherland, and Russian Messenger with the first publications of Dostoevsky's novels, and other materials.